Thungasilk International is a vertically integrated group with its processing facilities supported by a hi-tech infrastructure.

Its assembly line is as follows.

- Traditional hand looms to the latest and most advanced Hi-Tech German Shuttle less weaving machines ( of Dornier make )

- Flatbed screen to latest Japanese digital printing machines ( of Mimaki make)

- Delicate hand embroideries to the latest multi-head computerized embroidery machines ( of Barudan and SWF make )

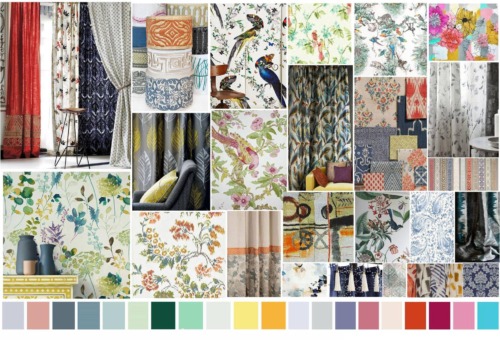

We do a research of current trends ( at various textile exhibitions, industry trend setters / high end designers / customer specification ) and freeze on the design trend or thyme for the fourth coming season.

Based on the shortlisted thymes, our designers do a extensive search in various design books / industry leaders / main customers, etc., and develop a mood board ( which will used as design inspiration, colour pallet, fabric type and repeat size ).

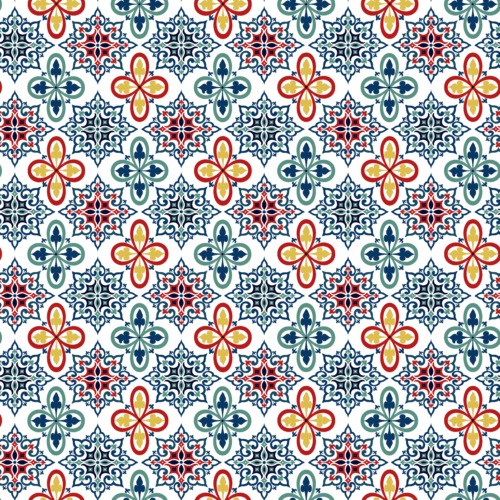

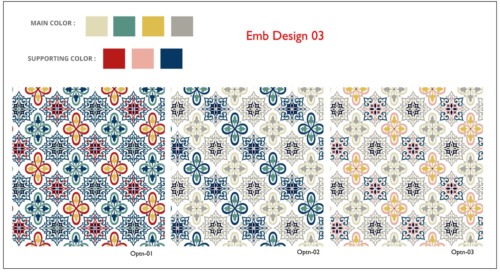

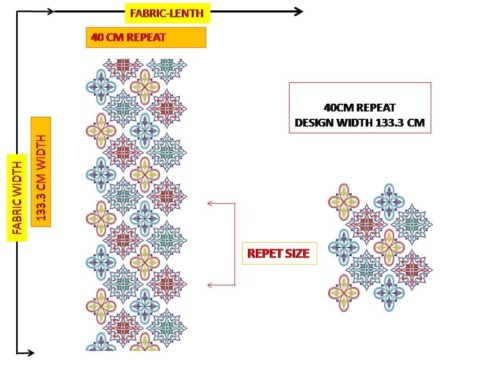

Based on the mood boards – our designers create a unique hand drawn actual size design.

This developed design goes through another round of evaluation to decide, whether it must be developed into a dobby / jacquard / embroidery / print ) along with the possible trend colours.

Then the design is punched ( using various designing software’s ) and a 3d simulation is created to check for flaws and further design enhancement.

Then a strike-off is developed.

After which the actual sample is developed and presented to the customer.

Origins of Silk & The Silk Road

The origins of silk date back thousands of years with historical documentation being the only means of understanding where the practices of cultivating and weaving silk fibers harvested from the cocoons of various moths began. Not all countries and regions were as meticulous in their practices of recording and collecting details of their cultures; making the true history of silk somewhat difficult to discern. Most historians and archeologists, however, would agree that the practices and traditions of silk evolved in ancient China.

CHINA

The origins of silk date back thousands of years with historical documentation being the only means of understanding where the practices of cultivating and weaving silk fibers harvested from the cocoons of various moths began. Not all countries and regions were as meticulous in their practices of recording and collecting details of their cultures; making the true history of silk somewhat difficult to discern. Most historians and archeologists, however, would agree that the practices and traditions of silk evolved in ancient China.

The secret of silk, and China’s silk production, lies in the indigenous varieties of wild silk moths—one in particular, the blind, flightless Bombyx mori. The original wild ancestor of this cultivated species is believed to be Bombyx mandarina Moore, a silk moth living on the white mulberry tree, and unique to China. The silkworm of this particular moth produces a thread whose filament is smoother, finer and rounder than that of other silk moths and can be reeled as a long, continuous and stronger thread than the filament produced from other species of moths.

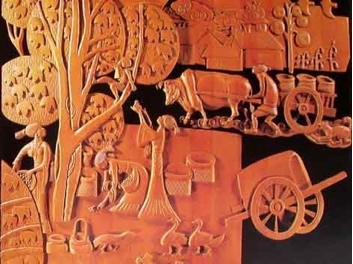

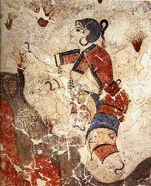

During the Shang dynasties (1766-1401 BC), as trade opened westward, silk production expanded to other cultures, utilizing other types of cocoons. During this time period, pictograms, which were inscribed on oracle bones and tortoiseshell, often depicted sericulture and the importance of silk. Stories of offerings being made to the Silkworm Goddess indicate the regard for this highly esteemed textile. Reeling silk and spinning were considered household duties for women during this period, while weaving and embroidery were carried out in workshops as well as the home.

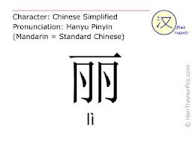

From ancient times, the Chinese evolved strict systems of rituals, and a philosophy of ‘Li’, which translates as the ‘virtue of orderliness and principled refinements’, or, the ‘virtue of propriety’. This all-encompassing philosophy has a relevance to the subject of silk since there was a hierarchy which influenced everything. Chinese history indicates that rules were drawn up regulating clothes, colors, fabrics and decoration, and punishments were meted out if these were violated. All motifs and colors had symbolic significance and were not merely decorative. Silk was considered the premier fabric of the upper class for their garments and their hangings, upholstery, throne seats and backs.

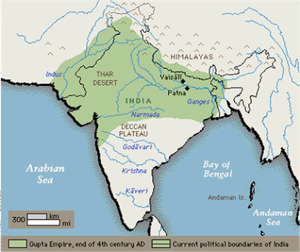

INDIA

Before we reach the destinations of the Silk Road around the Mediterranean, there is another ancient source of sericulture to consider that has been, and continues to be, a major contributor to the history of silk: India.

India’s textile history is rich and complex, with its silk production dating back 4000 years ago in the cities of Harappa and Mohenjo Daro. With a number of indigenous silk moths, many of whose cocoons are suitable for weaving, India’s silk history is vastly different from that of other countries. Known for famous textured silks (tussahs), early textured silks woven from wild cocoons are referred to as bark cloth and in the region around Mirzapur in Uttar Pradesh, tussahs are still known by this name. Although most of the wild moths must break the filaments of their cocoons to escape, one tussah moth, Antheraea pernyl, leaves an opening in the cocoon that it seals with sericin, so that the filament remains intact. As recently as the seventeenth century, Europeans believed tussahs were spun from a plant—hence the name ‘herba goods’ for these silks. The eminent Dutch botanist Rumphius was surprised to discover a chrysalis inside upon dissecting a “fruit”, ending the misnomer.

A Buddhist monk is credited with bringing the Chinese techniques of silk-reeling to India during the Gupta period (AD 400-600). It is presumed that he brought the eggs of the Bombyx mori, for the technique of reeling is only applicable to that particular type of cocoon. Records of temple donations given as offerings from silk weavers for increased silk production indicate that the weavers from India were eager to expand their craft. The customs surrounding the care and gathering of wild cocoons have become ritualized and have been so for thousands of years. India’s silk forests are considered sacred and tribal people protect the caterpillars from predators and harvest the cocoons. Silk was deemed by the Hindus to be a pure substance, so pure that it was not considered necessary to wash it before ceremonial use. According to the Mitakashara law, mere exposure was sufficient, for silk was ‘washed by air’. Orthodox Vaishnavite Hindus and Jains abhor the taking of life, and certain holy centers produce a silk known as matka (mutka) from the cocoons of moths which have completed their cycle and broken out of their cocoons. Since no killing is involved, this silk is considered unpolluted and suitable for the garments and ropes of the sacred processional chariots and for the ritual swings used during the Krishna festival of Sawan.

India is credited with developing the art of draping cloth, exemplified in the sari, which, although not the only form of Hindu feminine dress, may be thought to epitomize India internationally. The basic sari is a length of unsewn material that is draped, with over a hundred variations of doing so and regionally dictated decoration. A great deal of silk is produced and processed in southern India, and saris from the south are made of rich, heavy silk.

India is a vast repository of ancient motifs, techniques and ideas and is unique among silk-producing countries in the rich variety of silks it produces. India ranks second, after China, among mulberry silk producers and the largest proportion of this silk is produced in Karnataka. India is also the second largest producer of tussah silk. Sericulture is home-based in India as it is in China, and the low cost of labor contributes largely to the commercial strength of both countries. In recent years, government-supported bodies have worked hard to promote the revival of hand skills in danger of dying out, and western designers have turned to India for special textile finishes and embroidery details.

JAPAN

During the Shang dynasties (1766-1401 BC), as trade opened westward, silk production expanded to other cultures, utilizing other types of cocoons and India and China linked East and West through its silks. Around the first century AD, it is documented that along the East-West trade routes that connected India with the Near East and ultimately with the Mediterranean, Indian traders were actively importing Chinese silks and exporting Indian wild silks and fine cotton muslins along these perilous land and sea routes where many lives and cargoes were lost.

“The garment was the person; it was the direct expression of his or her personality” was Lady Murasaki’s remark in The Tale of Genji (Heian period, 794-1185 AD) which offers us an insight into the role of silk in Japan. It is uncertain when the Japanese sericulture began with the indigenous Yamamai silk moth, but Chinese history indicates that its silk technology and the Bombyx mori reached Japan around 28 BC. By Lady Murasaki’s era, silk was a long established feature of elegant life and the kimono was the most important Japanese garment. It was worn by fashionable ladies, sometimes as many as twenty kimonos at a time, all made of the thinnest, finest, most transparent silk, giving a rainbow appearance as the coloring of each layer melted into those above and below. Like the Chinese, silk garments were reserved for the upper class and the ordinary Japanese people dressed in garments that were homespun of hemp and ramie.

The introduction of Buddhism to Japan, sometime after 500 AD, is important in silk history because silks are preserved in the temple treasuries and have been carefully recorded and conserved ever since they were given, either as valued gifts themselves, or as wrappings for precious offerings. Silk fabrics are still seen as a precious commodity, whether in modern day or history.

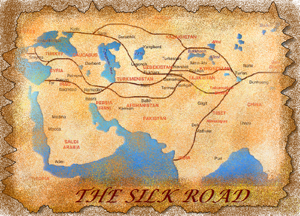

As trade routes became the highways of ancient times for merchants, artisans and craftsmen to bring their wares, goods, materials, supplies, cultural beliefs and practices from the eastern regions of Asia to Western Europe, a very distinct route emerged that further expanded the role of silk in history. The Silk Road was named for this specific commodity as these trade routes developed, and the East-West passage brought sericulture to Central Asia and eventually, Western Europe.

The earliest silks discovered along this route date back to 500-400 BC in the Altai Mountains. While we do not know the antiquity of sericulture outside China, we do know that varieties of silkworms were introduced to Central Asia during the Han period and eventually made their way to the region known as the Iranian Plateau. Frequently traveling together, silk, spices and rare treasures made their way by land routes through Persia from the Central Asian passages or by ship through the Persian Gulf to the ports at the mouths of the Tigris and Euphrates. From there, they were transported to Syria, the prime Mediterranean point for dispersal of Eastern luxuries. The northerly land routes carried Chinese silks, while Eastern vessels brought India’s wild silks.

EAST TO WEST EXPANSION

The Caucasus, Armenia, and Gilan south of the Caspian formed part of the ancient Silk Road long before its ‘official’ opening in the second century BC during the time of the Romans and the Han. Silk had traveled to the Mediterranean and Europe from Greek trading posts on the Black Sea, and has been found in the Danube region, embroidered and woven into garments of the Hallstatt culture of the 6th century BC, and in several other early sites.

The Parthian period (123-87 BC) indicates garments decorated with silk cord and patterns in silk fabrics were dominated by the pomegranate, the symbol of the Water Goddess Anahita. The Parthians gave way to the Sassanian dynasty, which worked hard to establish their own silk industry. Their weavers created highly distinctive designs and their influence can be traced through the centuries to the present day.

As knowledge of silk spread westward through the centuries, almost every country attempted sericulture and attempted to develop silk weaving. The luxury, beauty, refinement and attraction of silk are such that other countries over the centuries were focused on developing their own silk production as a means of strengthening their own trade.

While documented evidence proves that silk was imported and woven in ancient Roman times, it appears that the earliest attempts of sericulture in Italy took place in the Po Valley in the tenth century and in the area around Salerno during the first half of the eleventh century. The essentials of silk processing were known and used in the Byzantine and Islamic empires, and it seems that in southern Italy, most of the work of mulberry culture was carried out by Jewish, Greek and Arab immigrants who brought their knowledge of silk production from the Near East. The merchants and weavers of Lucca, Venice and Florence, Italy controlled the silk trade and spectacularly developed silk weaving from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century during the Renaissance Period. Cultural developments and political strength were expressed in the beauty of evolving designs and new steps in the development of weaving. Italy still maintains a strong silk production today.

In Tours, France during the mid 1400’s, a self-made merchant prince, Jacques Coeur who eventually became the Minister of Finance, became discontent with merely importing silk fabrics and forged a partnership with Florence, Italy which marked the beginning of independent silk production in France. Fashion, the sustaining force of French silks, drew silk weavers from Italy and the French silk industry was founded on Italian expertise. The early woven silks produced in France had strong resemblances to that of the Italy, however in time, France began to produce their own distinctive weaves and patterns. Notably, the ‘Gros de Tours”–a strong heavy taffeta with a double weft and an interesting raised surface texture–made famous the silks of Tours “soieries Tourangelles”.

Many Western European countries attempted during the past several centuries to produce silk by developing silk weaving, and despite climate constraints, have attempted sericulture. The attraction and power and economics of silk are such that at one time or another in history these countries desired to strengthen their trade exports of this valuable textile. Denmark, Sweden, Spain, Russia, Ireland, Germany and England and more have all been part of the excitement of the silk industry and at present, France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland and the United Kingdom currently maintain production, with Italy being a producer on a world-scale market, behind China and India.

The history of silk has evolved with stories of discovery, artisanship, skill, travel, trade, religious and political meaning. Its influence, both past and present, suggest that this textile has been valued and treasured by many for thousands of years as an object of elegance and luxury and currency. Silk has been a valuable commodity and continues to sustain us culturally and economically on many levels.

HOW TO WASH AND CARE FOR SILK: THE COMPLETE GUIDE

How you wash, dry and care for your silk will ensure its longevity and maintain its shiny, soft qualities for many years to come.

Silk has long been one of the most sought after fabrics in the world, with many different uses from silk scarves and clothing to home decor, with the fabric even proving to be a good addition to your beauty sleep routine.

While silk holds the status of being one of the strongest natural fibers in the world, the fabric itself is incredibly delicate and requires special attention when it comes to cleaning, drying and storing to ensure it stays in pristine condition.

Does silk need to be dry cleaned?

For many years, it was thought that dry cleaning was the only way to properly care for silk – but silk can actually be washed at home. While the care labels on many silk products may instruct that the item be dry cleaned, this is simply down to the manufacturers preference.

Care labels are only required to state one method of washing, and this is to the discretion of the manufacturer. It makes sense that dry cleaning will typically be their preferred choice, as this limits the chance of mishandling and thus, complaints from customers who have ruined their perfectly good silk products. However, it’s important to note that should the label clearly state “dry clean only” then this should be followed as strict instructions.

Can silk be machine washed?

While it is entirely possible to machine wash silk, it isn’t recommended. Being such a delicate fabric, silk doesn’t tend to get along well with the constant turning motion of the machine drum. Silk should be handled with care, and throwing it in a washing machine can often be a little too rough.

Not only that, but it isn’t advisable to wash silk using the same cleaning products that you would on your cotton t-shirts. Silk should ideally be washed using special silk detergent, and washing machines can often hold onto residue from regular detergents or bleach from previous washes – all which risk damaging your silk.

If you are desperate to wash your silk articles in this way, ensure that your washing machine has a programme for washing delicate articles at a temperature of 30° – 40°. Although, before going ahead and throwing your delicate silks in the wash – ensure that you follow the above precautions beforehand, and wash the garment on its own.

1. How to wash silk

Before submerging your expensive silk into the washing bowl, there are a few careful considerations and preparations that need to take place.

1. Is your silk colour fast?

Silk takes to dying incredibly well, but while it can uphold the most stunning bold and vibrant patterns, printed silks can be prone to bleeding. To ensure that the print of your silk doesn’t spoil through the washing process, it’s important to test its colour fastness.

The easiest way to do this is to wet a small area of the fabric with a little bit of water (ideally somewhere which won’t be immediately obvious if it goes wrong!) and take a cotton bud to the wet area. By gently pressing, not rubbing, you will see whether or not the cotton bud picked up any colour residues. If it did, your silk will need to go to the dry cleaners. However, if your test returned a clean swab, you can go ahead and hand wash your silk as per the below instructions.

2. Pre-treat any stains

Stained your silk? You’ll want to see to that before getting involved in the washing process. Ideally, stains should be treated as soon as possible to give it the best chance of being removed.

The best way to remove stains from silk is with a 50/50 mixture of silk detergent and water. Soak a cotton bud with the solution, and gently rub it onto the stained area – don’t rub too vigorously, always handle silk with care! Repeat the same process on the backside of the stained silk, and you’ve completed the pre-treatment.

Note: Always seek out detergents specifically created for silk or delicate garments, and steer clear from all-purpose stain removers to avoid damaging your silk.

3. Hand washing silk

Once your silk has been prepared and you’re 100% certain it can be hand washed without bleeding, you may proceed. Ensure you have a thoroughly cleaned sink/bowl and fill it with cool water. Not too cold, not lukewarm but a nice middle ground between the two.

Add your silk detergent to the water by following the manufacturers instructions and sumberge your silk. Don’t go anywhere, as you won’t be soaking your silk for too long and it requires your attention at all times.

Constant movement is the key here, so you want to be gently swirling your garment in the water, ensuring that all areas are being washed, for approximately 4-5 minutes for small lengths of silk. Otherwise, larger garments may be soaked for up to 30 minutes.

4. Rinsing silk

Promptly take your garment out of the bowl once washed for the advised period of time, being careful not to squeeze the water out. Instead, drain the soapy water from the bowl and refill it with some more cool, clean water.

To remove any detergent residue, gently swirl your garment around in the water again for approximately one minute, ensuring that no soap is left behind. Repeat the process if necessary.

2. How to dry silk

You’re not going to need your tumble dryer for this one, as this method of drying silk is strongly advised against. Instead, silk should be air dried for the best results.

Firstly, you want to absorb any excess moisture by laying it out flat on top of a clean towel. Roll the towel up with the silk inside, and gently press down. Repeat the process with another clean towel until the silk is no longer soaking.

Once removed from the towel, lay the silk garment out flat on a drying rack without using any clothes pegs. The silk should be dried in the shade, as direct sunlight can cause its colours to fade.

Silk tends to dry quite quickly, and you should fine that your garment is dry within around 30-60 minutes.

3. How to iron silk

If your silk has air dried flat, you shouldn’t see many wrinkles or creases in it. However, a quick run over with the iron can help it to look brand new! Yes, steaming is usually the safest way to go about removing creases, but silk can be ironed just as well.

To avoid staining or damaging your silk, ensure that your iron and ironing board are clean and free from any water or liquids. Be sure to iron on the backside of the fabric, and stick to a low heat.

If your iron has a special silk setting, use that or set the temperature to around 148°C (300°F). Whatever you do, steer clear of the steam setting – we want to avoid any water droplets at all costs!

Top tip: Use a pressing cloth for ironing double-sided silk to avoid applying heat directly to the pattern on either side.

4. How to store silk

Now that you know how to properly wash and dry your silk, it’s important that you know how to store it correctly to maintain its quality in between wears and washes.

Silk generally should be stored in a cool, dark and dry place with adequate air circulation. Being a natural fibre, silk needs to be able to breathe so avoid packing your silk garments away in tightly sealed plastic bags. For best results, hang inside breathable cotton bags to avoid unwanted creases and wrinkles so that it’ll maintain its shape and be good to go for your next wear.

Finally, silk should always be clean before storing away. You don’t want to hang up any silk garments that may be stained, dirty or carrying natural oils as this can degrade the fabric over time and lead to damage.

Whether it’s a beautiful silk dress for a special occasion or luxurious silk bedding, investing in true silk products will last you a lifetime should you care for them properly.

Please note that this is a general guide to washing silk, and certain qualities may vary. Some silks are washable, for others dry-cleaning is recommended. If in doubt check with the store where you bought the fabric or garment.

|  |  |  |  |